Family First in Financial Focus: Non-Family Placements

A central goal of Family First is to ensure that when foster care placement is necessary, children are in families whenever safely possible.

Non-family settings can play an important role addressing a child or young person’s therapeutic needs.

Evidence shows that children placed with families—especially kin—experience better outcomes in stability, emotional well-being, and long-term development compared to those placed in institutional or group care settings. (Casey Family Programs. (2024, March 7). First placement with family. https://www.casey.org/first-placement-family-placement/).

To advance this goal and retain the role of non-family settings in promoting treatment, Family First significantly narrowed federal reimbursement for non-family foster care placements.

Family First’s New Restrictions on Non-Family Placements

Under Family First, Title IV-E foster care maintenance payments are now limited to two weeks for non-family settings, unless the placement meets one of four specified categories:

Supervised independent living arrangements for youth age 18 and older

Specialized settings offering prenatal, postpartum, or parenting supports for youth

Settings for children and youth experiencing or at-risk for sex trafficking

Qualified Residential Treatment Programs (QRTP) for children with demonstrated need

For the first three specified settings, states have broad discretion in defining criteria for the setting, provided they meet basic licensing and safety standards.

Qualified Residential Treatment Programs

QRTPs represent a new, more rigorous category of residential placement than settings previously eligible like group homes, with specific statutory requirements:

Accreditation

Licensed or registered nursing staff

Discharge planning and aftercare support

In addition, federal requirements include:

Independent clinical assessment within 30 days of QRTP placement;

Judicial review of placement appropriateness within 60 days; and

Ongoing documentation for any extended placements.

Failure to meet these process and documentation standards results in loss of federal reimbursement for the placement.

Background Check Requirements

Family First strengthened background check requirements for all non-family foster care settings. Title IV-E reimbursement is now contingent on completion of:

Fingerprint-based national criminal history checks; and

State abuse and neglect registry checks.

All adult employees of non-family settings must meet these standards for the placement to be eligible for federal funding.

Residential Family-Centered Substance Use Disorder (SUD) Treatment

Family First also created a new pathway for using Title IV-E funds to support residential family-centered SUD treatment:

States may claim Title IV-E foster care maintenance payments for a child placed with their parent in a licensed residential SUD treatment facility.

This policy is meant to prevent parents from having to relinquish custody when their child can accompany them to a treatment facility that serves both of their needs.

Up to 12 months of reimbursement is available.

Licensing is required, but not necessarily by the Title IV-E agency.

No income test applies.

Importantly, these placements must provide integrated services as part of the treatment model, including parenting supports and child development services.

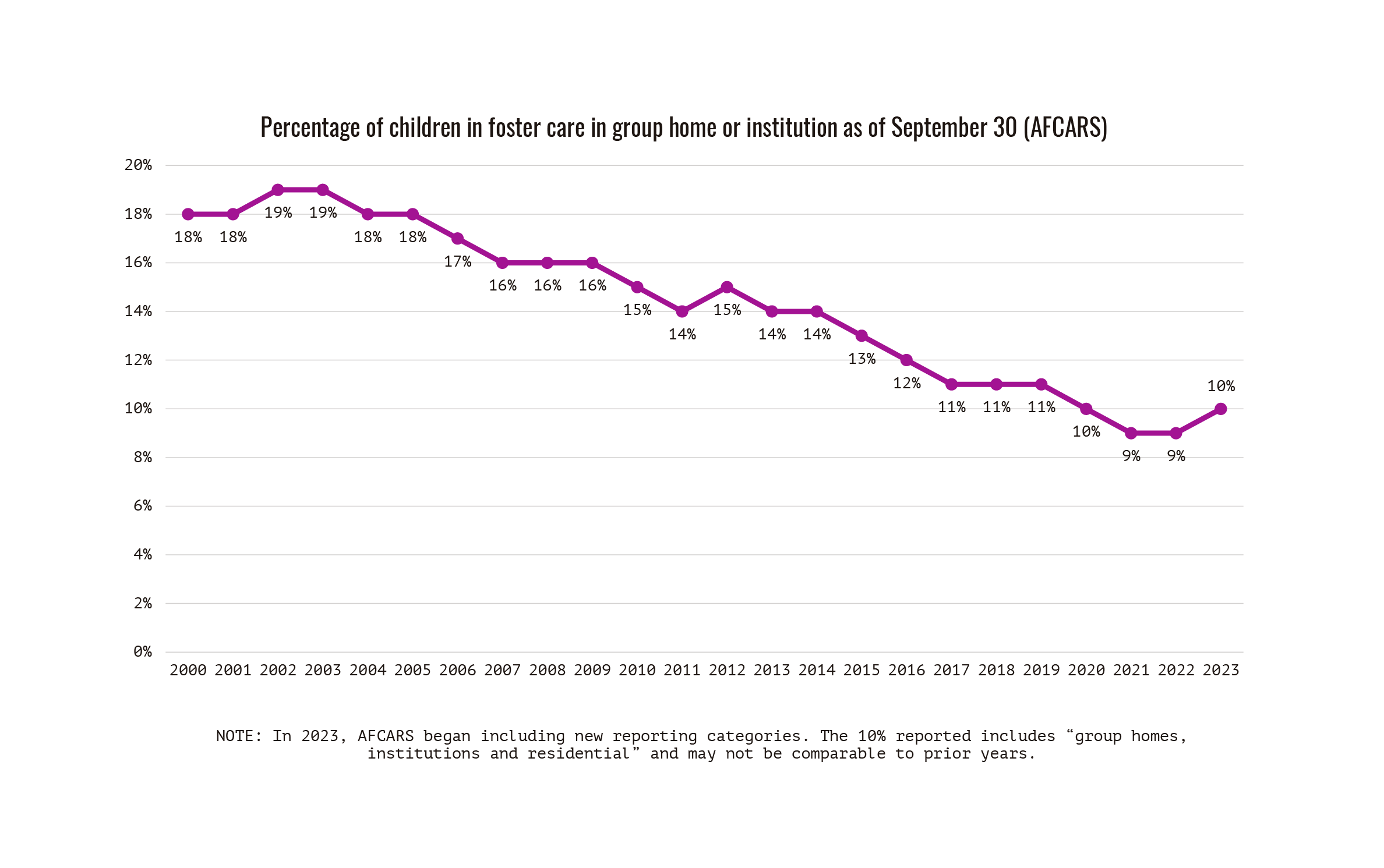

This graph shows over two decades of trends in non-family placements using AFCARS data.

Current Status and Participation

Assessing the impact of Family First on non-family placement trends remains complex:

Data limitations: States and tribes have only recently begun reporting placement-specific Title IV-E claims, limiting data accuracy and comparability.

Variability in reporting: Inconsistent state compliance and lack of historical baselines make longitudinal comparisons challenging.

Declining claims, with caveats: Available data indicate declining Title IV-E claims for non-family placements. But we don’t yet know if that’s less use of non-family settings, or cost shifting.

Despite these limitations, our project was able to develop the first-of-its-kind benchmark of expenditure and caseload data for non-family placements as defined by Family First.

We were able to analyze nearly half of all states and two tribes, focusing on those with data that our analytical team determined were sufficiently credible to include in our review.

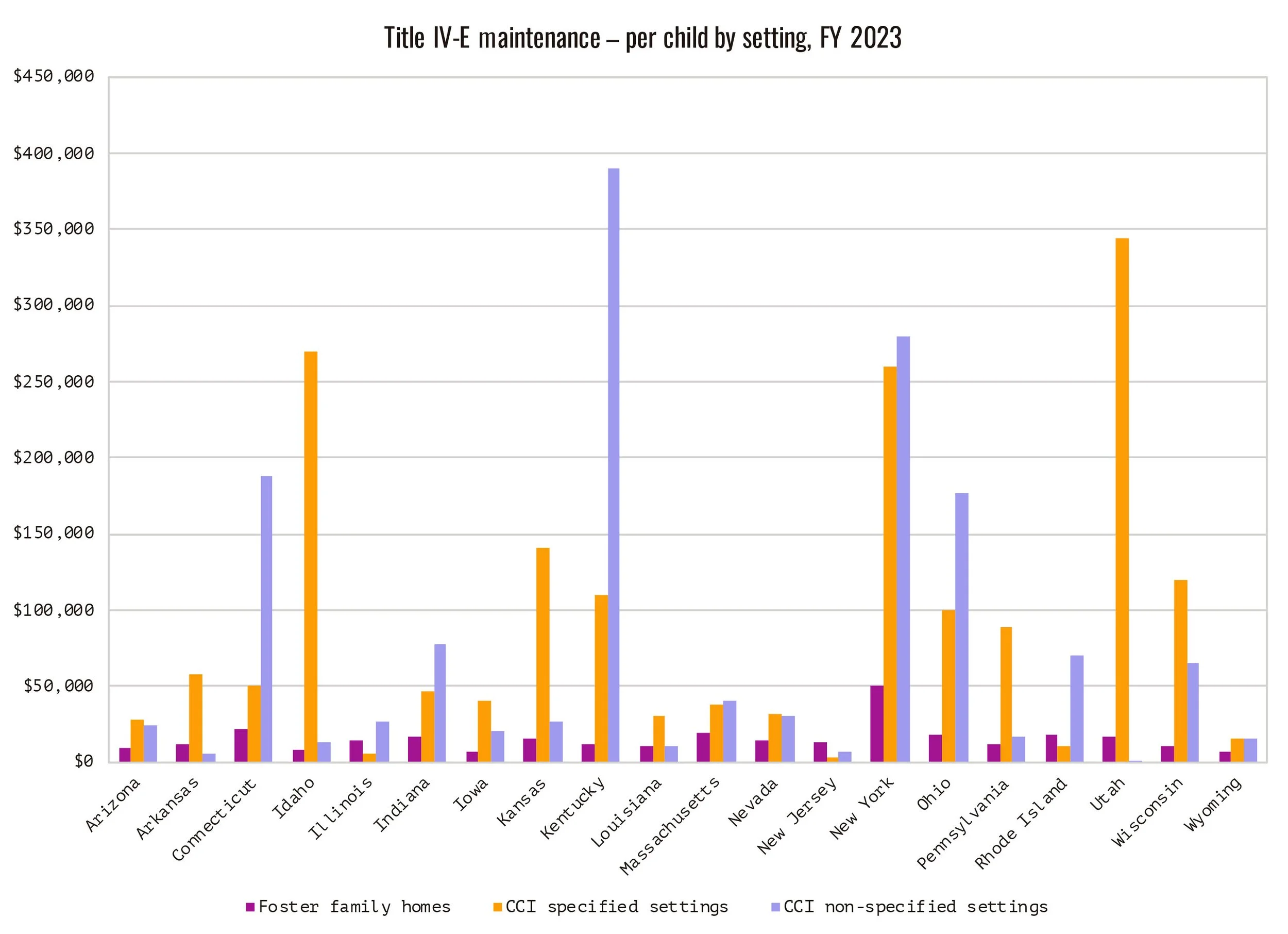

This is an important starting point for evaluating implementation and tracking trends, even with the caveats that accompany new data. From this we found average annual total per-child Title IV-E foster care maintenance spending by setting:

$17,454: Family foster homes

$83,383: Specified non-family settings (the new categories under Family First)

$54,559: Non-specified non-family settings (those grandfathered in)

Looking at this subset of states, we also were able to break out claims by setting, to see how much of each maintenance dollar went to each setting type:

77%: Family foster homes

12% Specified non-family settings (the new categories under Family First)

10% Non-specified non-family settings (those grandfathered in)

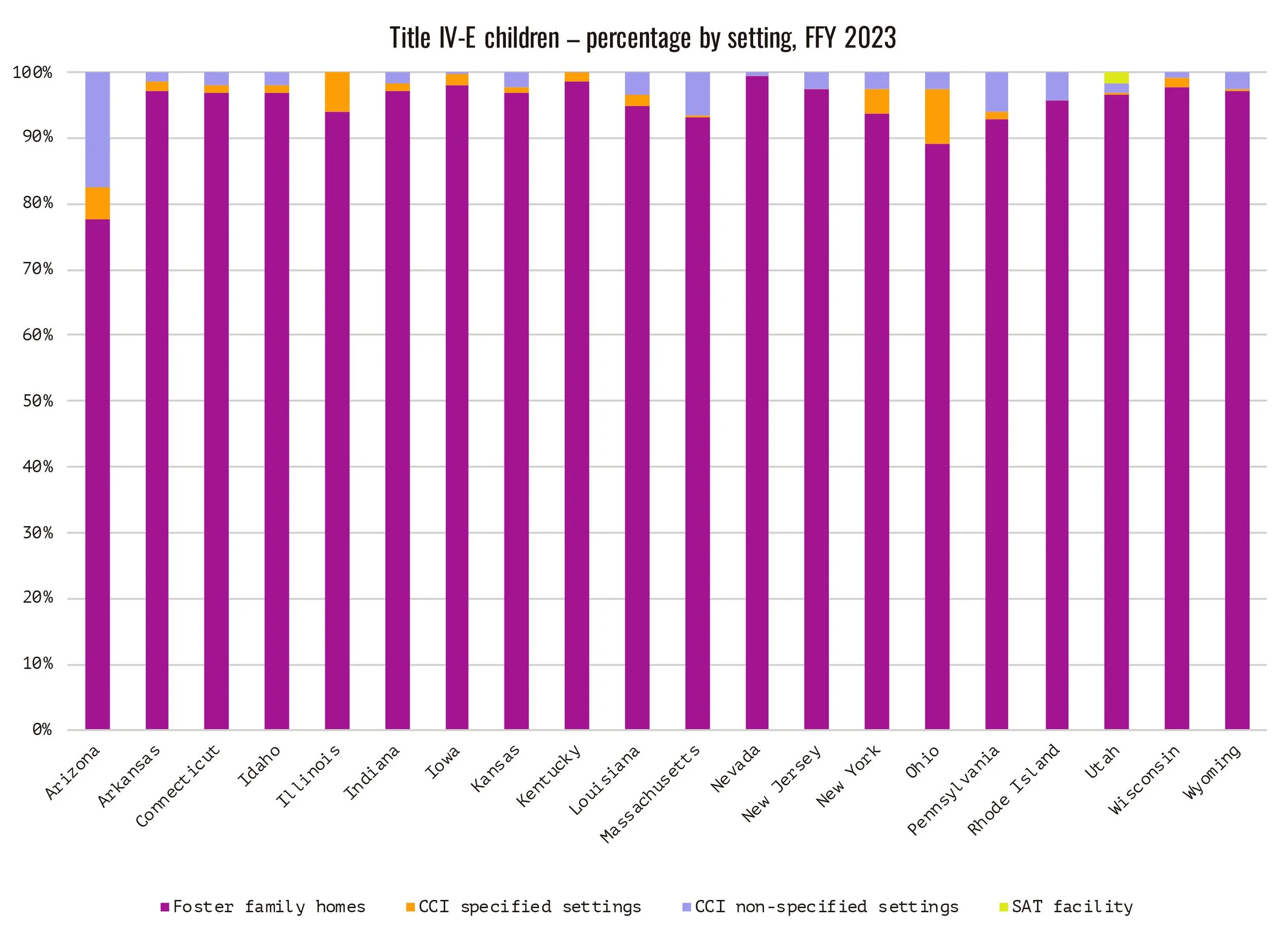

Finally, we were able to look at the counts of children for whom maintenance was paid, to see what proportion of covered children were in which settings:

93% Family foster homes

3%: Specified non-family settings (the new categories under Family First)

4% Non-specified non-family settings (those grandfathered in)

Barriers to Broader Rollout

Unclear Link Between Financing and Practice Change: It remains difficult to determine whether observed shifts in placement patterns reflect genuine changes in practice or are simply responses to new financing structures. This lack of clarity hampers efforts to evaluate implementation fidelity and real-world impact.

Ambiguity Between Outcomes and Compliance: Without robust evaluation mechanisms, it's challenging to assess whether the law’s emphasis on family-based placements is improving child and family outcomes—or merely resulting in procedural compliance and financing reclassification.

Diversion of Funds to Non-Eligible Placements: Some states continue to rely on alternative funding streams to support non-eligible placements, such as non-therapeutic group care. These financial workarounds complicate budget tracking, obscure accountability, and may undermine the law’s intent to prioritize family-based care.

Limitations in Federal Reporting and Data Transparency: Incomplete or inconsistent reporting from states, along with limited federal data transparency, restricts the ability to conduct rigorous, system-wide evaluations of Family First’s effects on placement practices and outcomes.