Family First in Financial Focus: Financing Shifts from Foster Care to Prevention

Family First promotes the prevention of unnecessary foster care by creating the Title IV-E Prevention Program. Early financial data suggest that Family First has started shifting federal spending from foster care toward prevention.

Prevention in Context: Aligning Federal Financing with Evidence and Fiscal Efficiency

Title IV-E of the Social Security Act remains the largest single source of federal child welfare funding, representing over half of all federal child welfare spending. It operates as a permanent, open-ended federal-state partnership.

Many children who would otherwise enter foster care can remain safely at home if the child or their family were provided services for mental health, substance use, or parent skills. This approach leads to improved family health and stability while reducing costs.

Before Family First, federal funding remained largely locked into a foster care-first financing paradigm. Family First allows Title IV-E funds to support preventing unnecessary foster care, driving a shift.

How Family First Supports Prevention

Beginning in FY2020, Family First gave states the option to use Title IV-E funding for three categories of time-limited, evidence-based supports to prevent unnecessary foster care:

Mental health services

Substance abuse prevention and treatment services

In-home parent skill-based programs

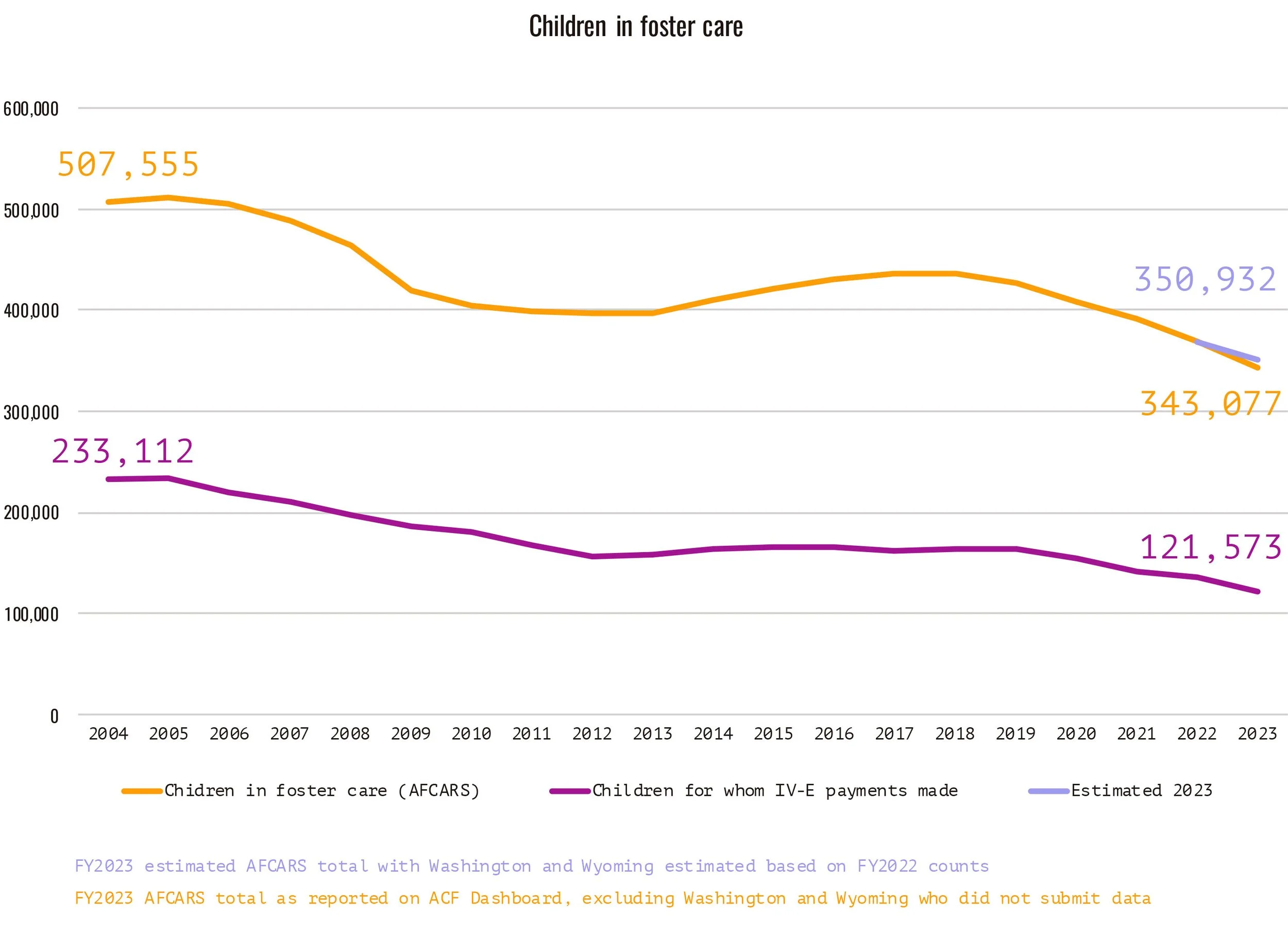

These reforms arrived at an inflection point. For twenty years, the number of children in foster care has been trending downward, while the federal government has covered foster care for fewer children.

This structural tension is eroding the stability of federal child welfare financing; the very category of services most funds are focused on is narrowing in who it can serve with each passing year.

This cost shift is the result of income-focused eligibility limits that don’t rise with inflation. This foundational aspect of financing policy drives the reduced federal share of child welfare financing over time, which has shifted more financing responsibility to state, tribal, and local governments.

This graph, drawing on AFCARS data, shows trends over time in the numbers of children in care and covered by Title IV-E.

In contrast, Family First prevention services are not income tested. Any child at risk of entering foster care, and their caregivers, may be eligible. This change doesn’t just change the eligible services; it offers a policy pathway to leverage increasing federal investment by redesigning the financing of child welfare systems.

This shift is not inevitable: while many provisions in Family First are required for states, Title IV-E-funded prevention is optional; states must have an approved plan outlining the services they intend to offer.

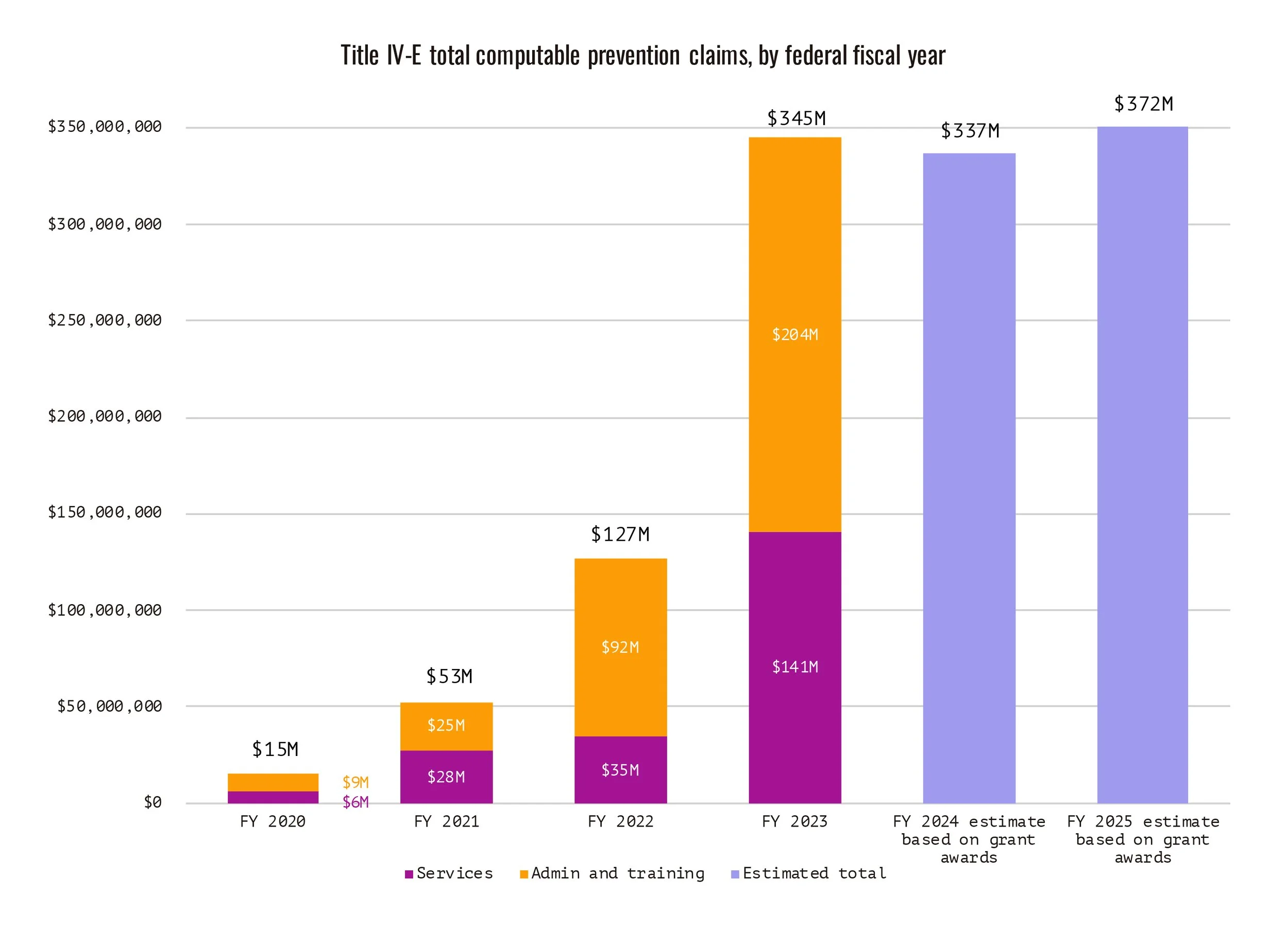

Developing a prevention program plan and building a locally-tailored service array takes time. While Title IV-E-funded prevention began in FY2020, implementation is still early, with varied progress across participating states.

Current Status and Participation

While overall federal prevention spending remains modest compared to foster care funding, expenditure data show notable shifts:

State Participation

Nearly all states have approved plans for implementing Title IV-E prevention.

As of 2025, 36 states and tribes were claiming Title IV-E funding for prevention.

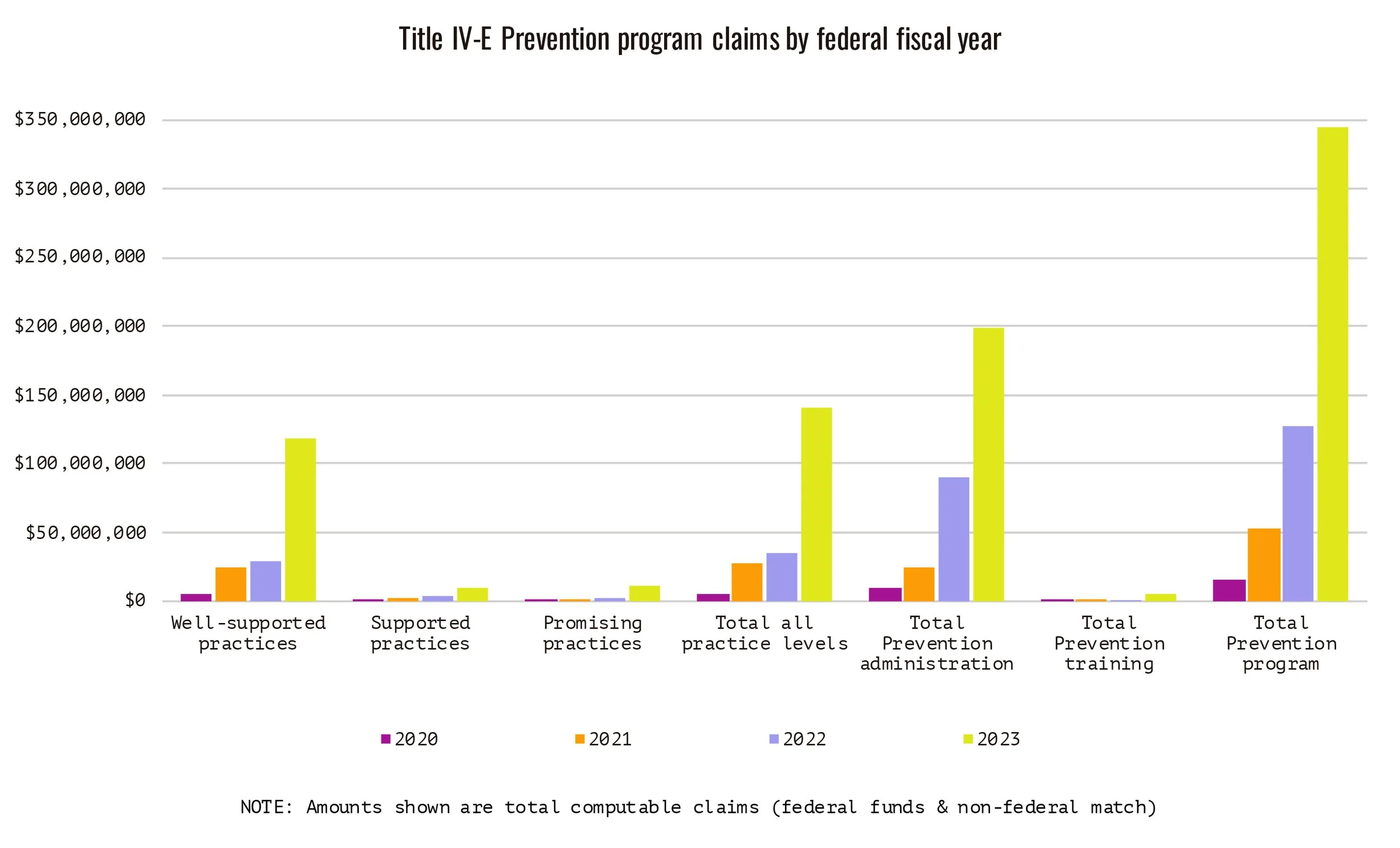

In the most recent year with available expenditure data, states and tribes drew down $173M in federal Title IV-E funding for prevention, compared to the $5.1B they drew down for foster care

This is modest in comparison, but the nominal dollar amounts also do not convey the early indicators of shifting and realignment of investment that other data do.

Analysis Focus

Shifting child welfare financing is complex, and simply looking at the dollars spent in a new optional federal program can mask notable early trends that are key signals for policymakers.

To surface that information, our team developed an analysis that looked not just at Title IV-E prevention, but other comparable spending within Title IV-E. That gave us a better vantage point to see trends relevant to Family First.

To analyze the full impact of Family First, nationally recognized child welfare financing expert Don Winstead led our analysis.

Don used a technique similar to ones used for evaluating spending shifts under the federal Title IV-E waiver demonstration program; an earlier bipartisan law that offered flexibility in testing approaches like those used in Family First.

Rather than look merely at the raw number of dollars spent, like the waiver evaluations we looked at relevant ratios; the proportion of spending on foster care to prevention.

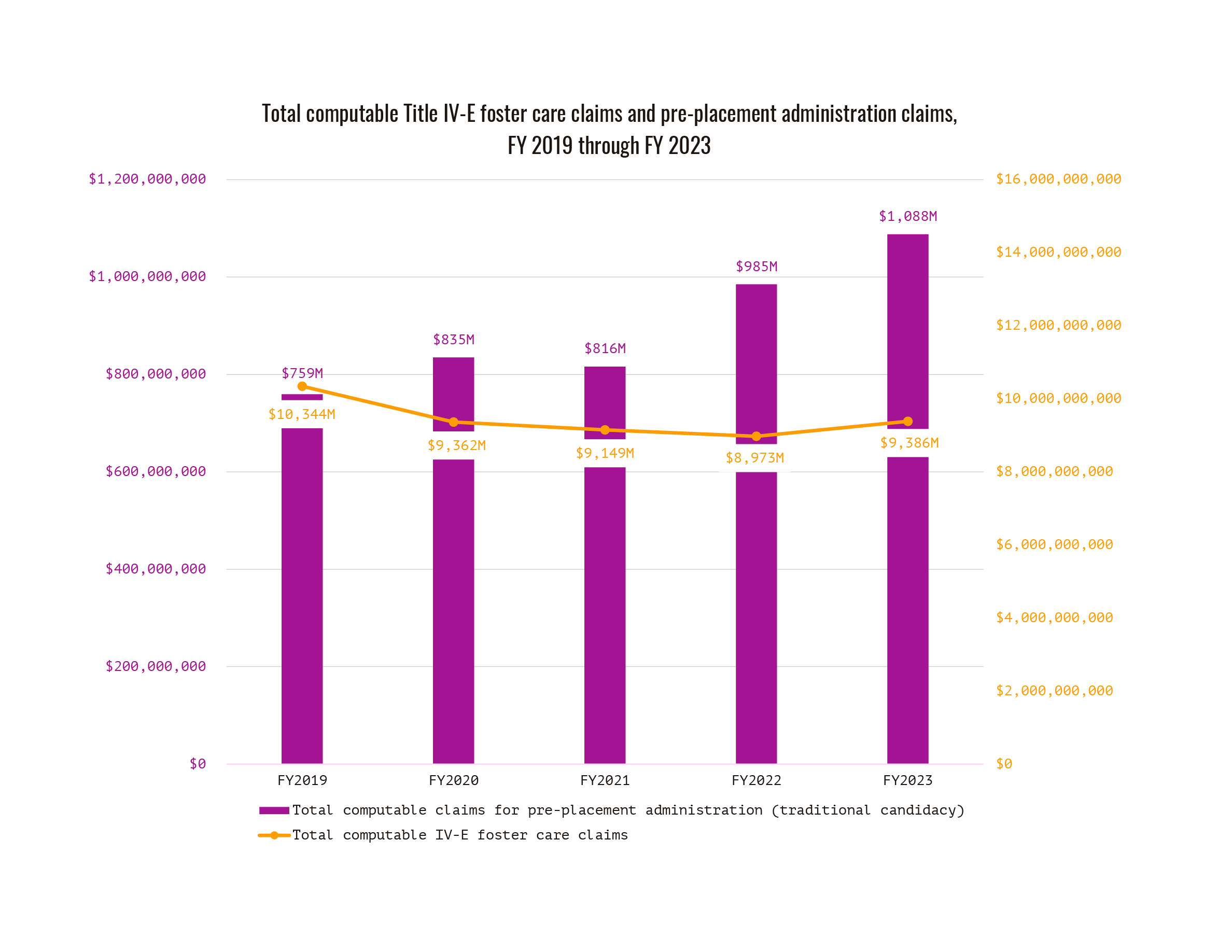

We also looked at an under-examined dynamic: so-called traditional candidacy under Title IV-E.

This longstanding option within the federal foster care program uses Title IV-E administrative dollars for family preservation; essentially offering financing for a limited set of prevention strategies similar to Family First.

While limited to Title IV-E eligible children, it is a way to use Title IV-E funds that is complementary to prevention under Family First.

This approach identified an emerging strategy, in which states use this approach as they ramp up implementation of Family First, maximizing federal resources to invest.

That ramp-up is evident in the fact that with each year a state used this approach, an increasing proportion of Title IV-E prevention-related spending was in Family First’s Title IV-E prevention program.

Key Takeaways

Our analysis shows key takeaways that put changes to Title IV-E prevention spending in context relative to foster care:

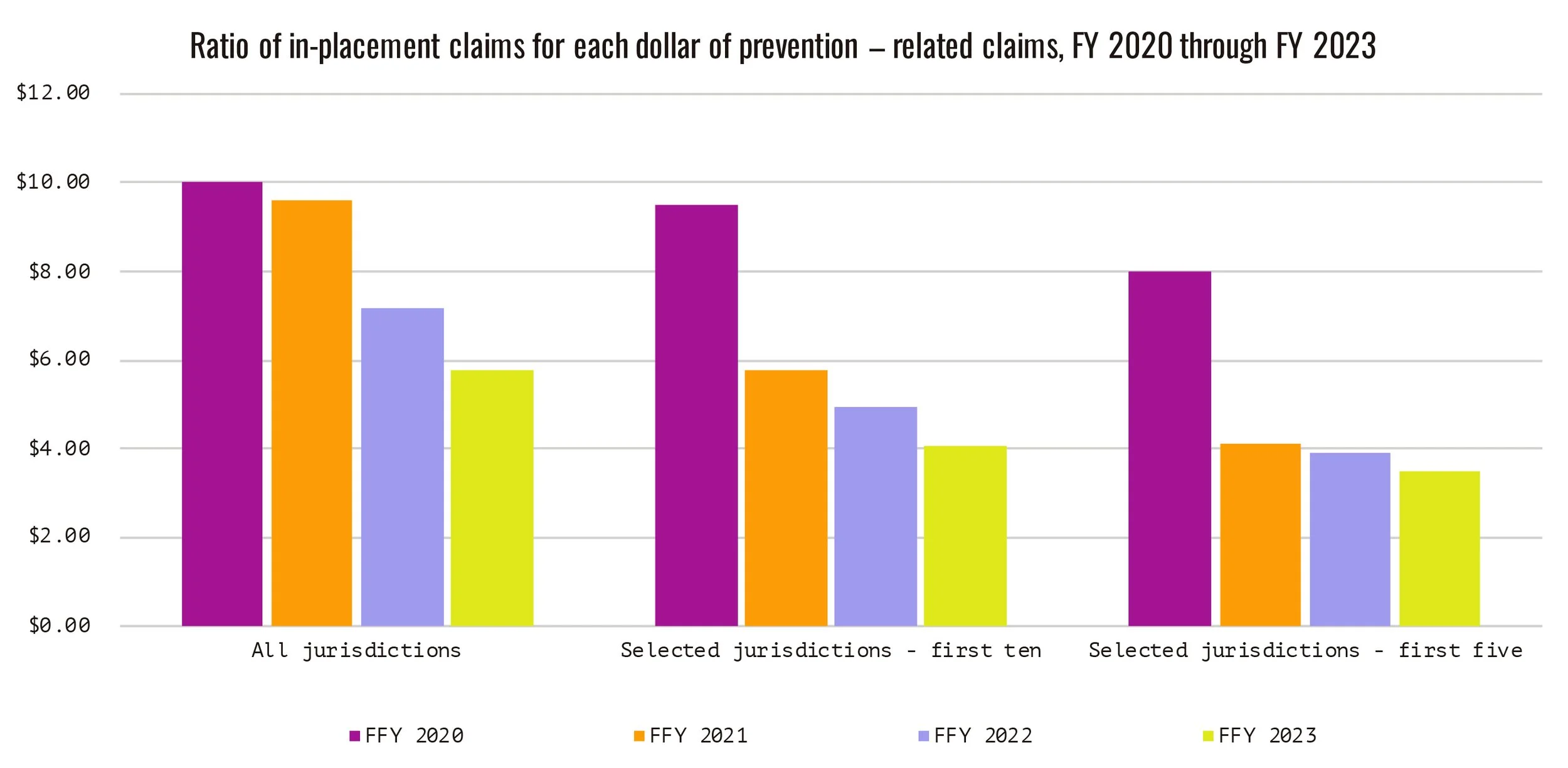

From 10:1 to 6:1: When Family First implementation began, states spent just over $10 on foster care for each $1 of prevention.

Within two years, this dropped to less than $6 for each $1.

This is a significant enough shift to suggest states are redirecting their investment of federal funds to align with the bipartisan focus of Family First.

First Mover Effect: The earliest implementing states have driven even sharper shifts, cutting this ratio by more than half.

These ratios offer an important benchmark; tracking them can indicate whether financing continues moving toward prevention over time.

This chart shows the ratio of dollars spent on foster care for each dollar spent on prevention. It shows that examined this way, dollars are shifting significantly away from foster care and toward prevention. This pattern is especially pronounced for those jurisdictions that started implementing Family First the earliest.

Factors Impacting Broader Rollout

Several dynamics will shape whether Family First’s prevention shift fulfills its potential:

Limited Service Array, Rate-Limited Implementation

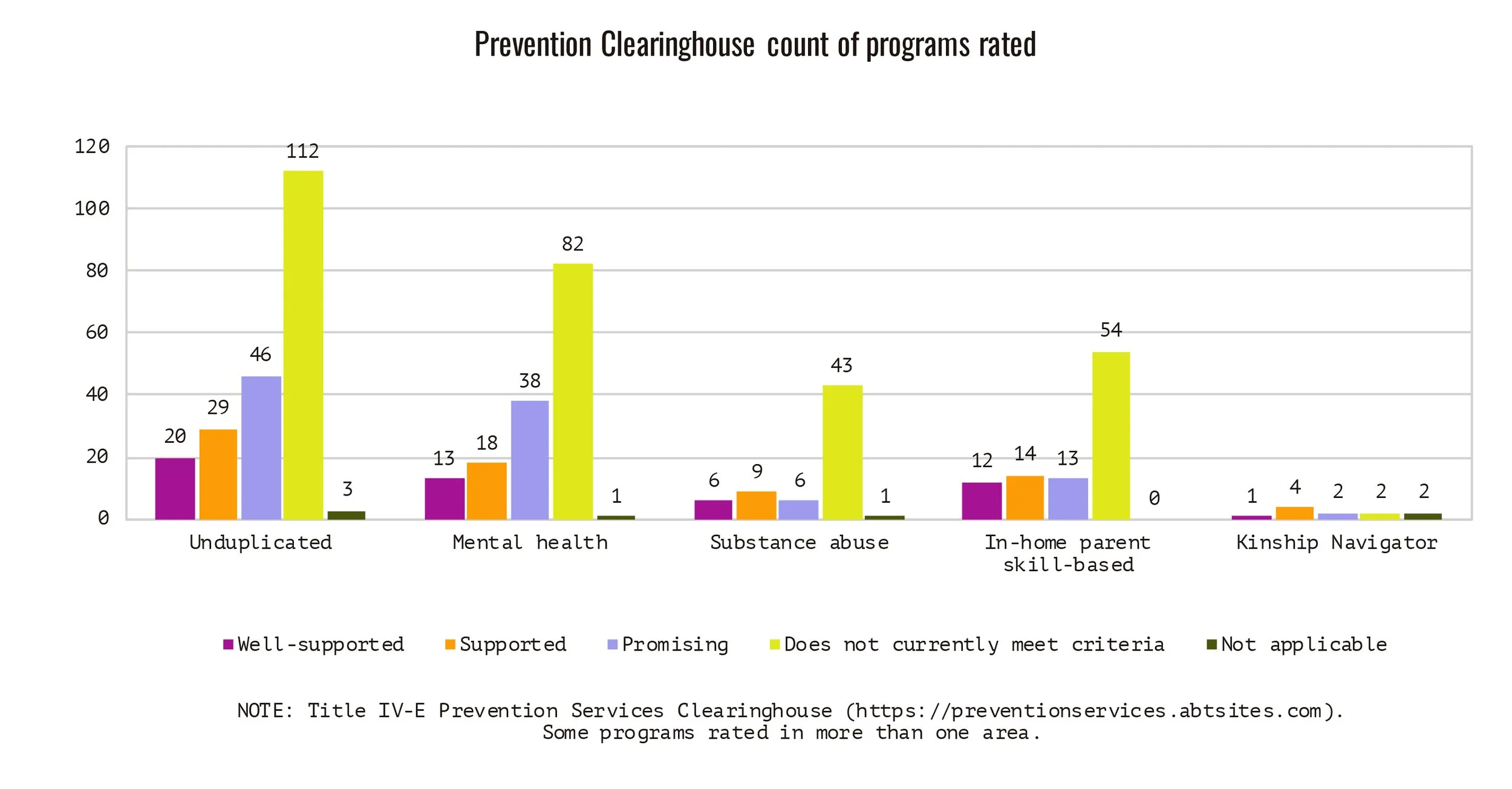

The Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse (Clearinghouse) determines which services are eligible for reimbursement, sorting them into three approved categories (promising, supported, or well-supported).

By systematically reviewing existing research, the Clearinghouse decides whether there is sufficient evidence that programs and services have a favorable impact on a series of child welfare related outcomes.

95/210. The Clearinghouse has approved only 95 of 210 programs it has reviewed, a 55% rejection rate.

Programs are rejected either because existing evidence shows their impact is insufficient on child welfare outcomes, or the quality of existing studies is insufficient to assess their impact.

As of FY2023, 85% of prevention claims were for the highest category of services. This tier, known as “well supported,” must have multiple randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental studies on their impact, showing sustained impact for at least one year.

Top tier limitations. While these programs have the most evidence for effectiveness, they are also costlier and less flexible to deploy, potentially limiting scalability. That highest category of evidence is also the only one that does not require ongoing program evaluation, which may also be influencing that choice.

Evidence≠Effect. Having the most evidence for a notable effect does not necessarily indicate having the evidence of being most effective.

Top tier limits. At least half of each state or tribe’s spending for this program must be in the top category. When combined with the higher cost of this category, state leaders face an understandable rate limiting decision to avoid inadvertently spending too much in another category.

These charts show ratings across the categories, as well as spending by category.

Candidacy Definitions

States define who qualifies as a “candidate for foster care,” a key eligibility factor.

Definitions vary widely; some states pursue expansive, community-based definitions, while others adopt more targeted definitions.

This definition reflects a significant policy choice, rooted in differing perspectives on the appropriate role of the child welfare system in serving families and the tradeoffs between serving more families by classifying more children as at-risk of entering care, and serving fewer children and families to avoid increasing families contact with the child welfare system.